Have you ever looked back on an experience and thought to yourself “damn, I wish I was more present. I wish I realised how lucky I was to be there”. It happens to me all the time, but not last week. Last week, I was there with Manoocher.

Sunday, November 19. I pack my rolls of film and get on a plane to Bari, Italy. I’m about to spend a week with award-winning photojournalist Manoocher Deghati and am feeling both nervous and excited. Manoocher’s life and body of work are nothing short of extraordinary. His career started in 1978 with the revolution in his native Iran, when he picked up his camera and photographed the streets. The Shah’s regime was overturned, Ayatollah Khomeini became the first supreme leader of the newly declared Islamic Republic and, with the help of the Pasdaran (Revolutionary Guards), instated a rule of terror and brutality. Manoocher courageously documented his country as well as the war with Iraq for years until one night, a phone call from an old acquaintance warned him that he had gone too far and was now considered an “enemy of Allah and the people”. Manoocher knew what that meant. He left Tehran the next morning, in 1985, and never went back.

Manoocher spent the following four decades photographing conflicts and social crises across the globe, winning prestigious awards along the way. He set up Agence France Press (AFP)’s photography department in Central America. He founded a school of journalism in Kabul with his brother Reza after the collapse of the Taliban rule. He worked in the Middle East for many years, mostly based out of Cairo and Jerusalem, and almost lost his leg — and his life — when he was shot by an IDF sniper. An Israeli surgeon saved the limb in an 8-hour-long surgery, after which Manoocher spent 18 months in rehabilitation at the Hopital des Invalides in Paris. There, he documented the lives of war veterans and met president Chirac, who granted him a French passport — one that would enable Manoocher to travel much more easily. His active life resumed. He met his wife Ursula in Syria on the site she worked on as an archeologist and that he was sent to photograph for National Geographic. He trained photographers for the UN in Kenya and moved to Cairo in 2011, to lead Associated Press’ photo operations in the Middle East. The Egyptian revolution broke out on his second day on the job, and Manoocher spent the following years coordinating hundreds of photographers across 20 countries in the region, covering years of unrest and revolution.

If you're interested in learning more about Manoocher's life and work, check out his new project. More on this below.Home

Monday, November 20. Manoocher’s home is now in the Valle d’Itria in Italy, where he lives on a farm with his wife and their daughter Clara. I am here for a week to learn about photojournalism1 and I stay in their trullo — a small stone house with a distinctive conical roof, typically Apulian. This is my first time in the region and I learn about the rivalry between the North and South of the country. The North of Italy is wealthier, industrialised, formal. The South is agricultural, burdened by underfunded infrastructure, and often left behind. I am told that cultural events rarely make it south of Rome, but I see a great deal of pride and warmth in the Apulian people. They stand proudly by their traditions and values, their produce and architecture. Even though my own Italian roots are in the Northern Emilia region, I quickly fall for the laidback spirit of the South — a sentiment that drew Manoocher and his family to this land. Their farm lies on the Strada Cicerone, and I find this quote from Marcus Tullius Cicero in the guest information folder:

If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need.

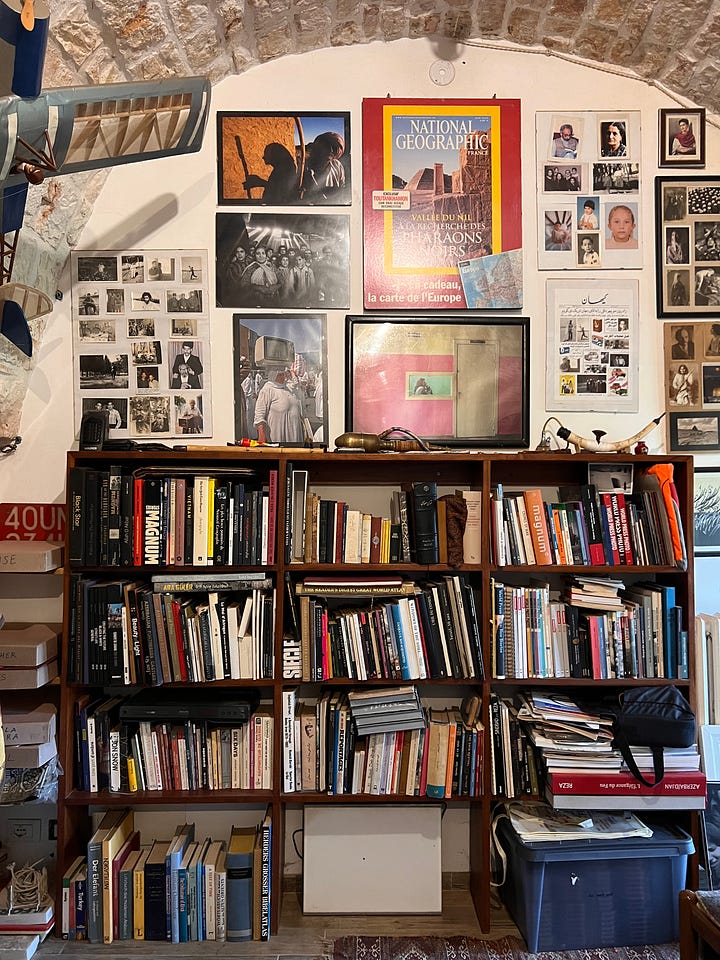

This sets the tone for the week. Books are everywhere — in the trullo, by the fireplace, and in our conversations. The household speaks and reads in English, Italian, German, French, and Farsi. Ursula wrote a few books, including a biography of her husband that I read avidly ahead of my trip. Clara is a voracious reader with a special appetite for Lord of the Rings. Manoocher doesn’t write, his medium really is photography. He speaks eight languages but is most fluent in images, and his studio overflows with photo books which he generously shares with me to study as homework. The garden is also a powerful presence — the farm has fruit trees, vines, herbs, swings, and even a yurt. It has ducks and chickens, cats, and Sirius the black dog (another literary reference that Harry Potter fans will understand). We eat fresh eggs from the coop in the morning, and bread with homemade jams. The family produces their own olive oil and their own white wine. When I ask Manoocher if their oil has a name, he gives me a curious look and replies olive. This, too, sets the tone for the week. They work hard and live sustainably on the farm, close to their land and community. They cook with their olive oil, give it to friends in batches when they come visit, bring bottles to parties where their neighbours contribute their own produce, and by no means do they intend to commercialise any of it. Puglia has given Manoocher and his family a life rich in flavour and meaning.

In the studio

First lesson in Manoocher’s studio. He starts with a rhetorical question — you know what photography means, right? I blush, embarrassed, wondering how I made it to 30 without ever asking myself where the word came from. It means writing with light.2 Of course it does. For the next few hours and days, Manoocher teaches me about his craft. Documentary photography is not only about pressing the shutter. It is about being resourceful enough to be in the right place at the right time in the most adverse conditions, and about knowing the history, geography and politics of an ever-evolving world to get a sense of how its narrative might unfold. It’s about putting the individuals back at the centre of abstract tales and connecting with them, regardless of their affiliations. Manoocher believes the craft to be deeply subjective, and recounts countless press conferences where dozens of journalists would sit right next to each other to capture the exact same scene — whether a handshake, a signature, a speech — and get completely different shots. Every single photograph is a unique historical document that has inherent value. I find it comforting to hear, as I sometimes feel self-conscious about the number of photos I take (everywhere! all the time!). This is the validation I had unknowingly been longing for: taking pictures is always important. Permission to keep shooting.

I’ve seen your photographs

Time for a break, we head to the kitchen. Ursula is a guardian angel who always leaves hot tea on the fire. Manoocher makes a comment in passing — I had sent him my portfolio prior to coming to the course. I’ve seen your photographs, he says. I know what your problem is. Uh-uh. You’re too shy. You can’t be shy as a photographer. It’s ok to be shy in real life, but not behind the camera. You have to overcome this. A simple comment that seems obvious but has been a real inflection point. I was never been able to articulate this malaise, but looking back on the photos I’ve taken over the years, all I can see now is the lack of courage they represent. Hidden faces, long shadows, empty landscapes. Robert Capa said “if your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough”. I’m not a photojournalist and have therefore always questioned my legitimacy in getting closer — but no more. Manoocher doesn’t believe in the notion of amateur either: if you photograph, you’re a photographer. This rings true to me. My family always taught me that you either do things or you don’t, there is no in between. I make it my mission for this week (and life?) to be more courageous. Manoocher and I only have 5 hours of class a day, which leaves plenty of time to wander in nearby towns and practice. We also shoot together on occasion and I learn a lot from watching him move through the cities we visit. They are living and breathing organisms, and Manoocher dances with them. He greets people on the street, asks fishermen how big their nets are and what kind of fish they’re after, he asks for direction, enquires about the rules of a card game being played in a room with an open door. Here is another lesson — you think you’re more respectful when you don’t disturb people, when you ignore them, while in fact it’s quite the opposite — you respect them more by engaging with them.

Our workshops are different every day. From the ethics of photography, to editing (we do some work for his students in Iran, helping them pick 10 of their best photos to create powerful stories), to visiting the remarkable World Press Photo exhibition in Bari (a must see). Ursula teaches me some art history and points to our inner cultural and artistic bias: the art we’re exposed to over time informs how we take and perceive images and photographs. We discuss how art and documentary photography share the motive of wanting to get to the essence of the human experience. From Ursula’s slide, I copy the following quote from Terry Pratchett:

It’s not what a horse looks like, but it’s certainly what a horse is.

Manoocher says that a portrait is not about showing someone’s face, but about showing who they truly are. Throughout the week, I think about how much information each picture contains. I used to see my camera as a tool to practice what I call “radical amazement”, a device that reminds me to open my eyes and notice moments of beauty. A tool for presence. On Thursday, November 23, I change my mental model and write in my notebook: STORY > BEAUTY.

Magic and pasta

Another quote caught my attention in the trullo’s information booklet, this one attributed to Italian cinematographer Fellini:

Life is a combination of magic and pasta.

A light-hearted line which I wholeheartedly believe. Not necessarily one that I’d expect to see in the home of a war photographer and an archeologist, people who have studied and documented the world’s biggest historical events, most violent conflicts and dictatorships. Or perhaps I should not be surprised, and the very people who have witnessed the great dangers of fundamentalism, of self-serving corrupt politicians, who have chronicled human rights and freedoms being confiscated, those are the people who know the importance of enjoying the simple things that make life quite magical. And that includes pasta. On our last day, we decide to do some food photography, which I anticipate with great enthusiasm. Ursula makes fresh pasta with a bit of flour, an egg from the coop and some water. For the sauce, we go for “rosso” (red, or tomato-based) and use the fresh mussels we bought earlier in Taranto. The ingredient list is simple and, once again, hyper-local: their own olive oil and wine, onion, garlic, parsley, passata and pepper. Manoocher spots the almost-untouched bottle of wine used for the sauce and is excited to pour it into glasses for us to enjoy with the meal. This particular bottle of white wine is infused with clary sage flowers which makes it even more festive. Once again, it’s about the little things.

Eyewitness

Manoocher’s legacy is not limited to his own photographs. He has also been teaching and training countless of photographic talent globally — in Iran, where he still mentors a number of photographers today, but also in Bosnia, Afghanistan, Central America and the Middle East. Teaching has always been a big part of his life. But his body of work is in itself legendary, and I feel lucky to have met him right as he is starting to work on a new project ahead of his 70th birthday — a retrospective photo book. It will contain a collection of images from his archive, his biography in the form of a novel, and will be edited by Sarah Leen (former Director of Photography for National Geographic). If the book reflects the qualities I’ve witnessed this week — genuine curiosity, honesty, and a profound humanity — it will be a very special one. You can join me by adding your name to the list of supporters here:

https://vawaa.com/artists/manoocher-photojournalism-italy

Phos (genitive: phōtós) meaning “light”, and graphê meaning “drawing or writing”.